Brightest Explosion Ever

Recorded

from RedNovaNews Website

2005/02/18

NASA -- Scientists have detected a flash of

light from across the Galaxy so powerful that it bounced off the Moon

and lit up the Earth’s upper atmosphere. The flash was brighter than

anything ever detected from beyond our Solar System and lasted over a

tenth of a second.

NASA and European satellites and many radio telescopes

detected the flash and its aftermath on December 27, 2004. Two science

teams report about this event at a special press event today at NASA

headquarters. A multitude of papers are planned for

publication.

The

scientists said the light came from a "giant flare" on the surface of an

exotic neutron star, called a magnetar. The apparent

magnitude was brighter than a full moon and all historical star

explosions. The light was brightest in the gamma-ray energy range, far

more energetic than visible light or X-rays and invisible to our

eyes.

Such a close

and powerful eruption raises the question of whether an even larger

influx of gamma rays, disturbing the atmosphere, was responsible for one

of the mass extinctions known to have occurred on Earth hundreds of

millions of years ago. Also, if giant flares can be this powerful, then

some gamma-ray bursts (thought to be very distant

black-hole-forming star explosions) could actually be from neutron

star eruptions in nearby galaxies.

NASA’s newly launched Swift satellite and the

NSF-funded Very Large Array (VLA) were two of many

observatories that observed the event, arising from neutron star SGR

1806-20, about 50,000 light years from Earth in the constellation

Sagittarius.

"This might

be a once-in-a-lifetime event for astronomers, as well as for the

neutron star," said Dr. David Palmer of Los Alamos National

Laboratory, lead author on a paper describing the Swift observation.

"We know of only two other giant flares in the past 35 years, and this

December event was one hundred times more

powerful."

Dr. Bryan

Gaensler of the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics in

Cambridge, Mass., is lead author on a report describing the VLA

observation, which tracked the ejected material as it flew out into

interstellar space. Other key scientific teams are associated with radio

telescopes in Australia, The Netherlands, United Kingdom, India and the

United States, as well as with NASA’s High Energy Solar

Spectroscopic Imager (RHESSI).

A neutron star is the core

remains of a star once several times more massive than our Sun. When

such stars deplete their nuclear fuel, they explode -- an event called a

supernova. The remaining core is dense, fast-spinning, highly

magnetic, and only about 15 miles in diameter. Millions of neutron stars

fill our Milky Way galaxy.

Scientists have discovered about a dozen ultrahigh-magnetic

neutron stars, called magnetars. The magnetic field around a

magnetar is about 1,000 trillion gauss, strong enough to strip

information from a credit card at a distance halfway to the moon.

(Ordinary neutron stars measure a mere trillion gauss; the Earth’s

magnetic field is about 0.5 gauss.)

Four of these

magnetars are also called soft gamma repeaters, or SGRs,

because they flare up randomly and release gamma rays. Such episodes

release about 10^30 to 10^35 watts for about a second, or up to millions

of times more energy than our Sun. For a tenth of a second, the giant

flare on SGR 1806-20 unleashed energy at a rate of about 10^40

watts. The total energy produced was more than the Sun emits in 150,000

years.

"The next

biggest flare ever seen from any soft gamma repeater was peanuts

compared to this incredible December 27 event," said Gaensler.

"Had this happened within 10 light years of us, it would have severely

damaged our atmosphere. Fortunately, all the magnetars we know

of are much farther away than this."

A scientific

debate raged in the 1980s over whether gamma-ray bursts were star

explosions from beyond our Galaxy or eruptions on nearby neutron stars.

By the late 1990s it became clear that gamma-ray bursts did indeed

originate very far away and that SGRs were a different

phenomenon. But the extraordinary giant flare on SGR 1806-20 reopens the

debate, according to Dr. Chryssa Kouveliotou of NASA Marshall

Space Flight Center, who took part in both the Swift and VLA

analysis.

A

sizeable percentage of "short" gamma-ray bursts, less than two seconds,

could be SGR flares, she said. These would come from galaxies within

about a 100 million light years from Earth. (Long gamma-ray bursts

appear to be black-hole-forming star explosions billions of light years

away.)

"An answer

to the ’short’ gamma-ray burst mystery could come any day now that

Swift is in orbit", said Swift lead scientist Neil Gehrels.

"Swift saw this event after only about a month on the

job."

Scientists

around the world have been following the December 27 event.

RHESSI detected gamma rays and X-rays from the flare. Drs.

Kevin Hurley and Steven Boggs of the University of

California, Berkeley, are leading the effort to analyze these data.

Dr. Robert Duncan of the University of Texas at Austin and Dr.

Christopher Thompson at the Canadian Institute for Theoretical

Astrophysics (University of Toronto) are the leading experts on

magnetars, and they are investigating the "short duration"

gamma-ray burst relationship.

Brian Cameron, a graduate

student at Caltech under the tutorage of Prof. Shri Kulkarni,

leads a second scientific paper based on VLA data. Amateur

astronomers detected the disturbance in the Earth’s ionosphere and

relayed this information through the American Association of Variable

Star Observers.

|

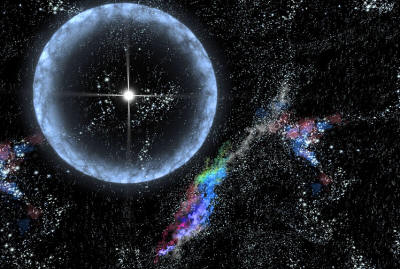

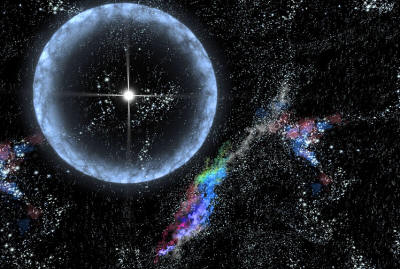

Gamma Ray flare expanding from SGR 1806-20

and impacting Earth’s atmosphere. Credit: NASA

|

|

An artist conception of the SGR 1806-20

magnetar including magnetic field lines. Credit:

NASA |

|

SGR-1806 is located about 50,000 light years

away from Earth in the constellation Sagittarius. Credit:

NASA |

|

Swift is a first-of-its-kind multi-wavelength

observatory dedicated to the study of gamma ray burst (GRB)

science. Credit: NASA |

|

High resolution, wide-field image of the area

around SGR1806-20 as seen in radio wavelength. Credit:

NASA |

Videos and

Animations

1)

Artist conception of the December 27, 2004 gamma ray flare expanding

from SGR 1806-20 and impacting Earth’s atmosphere. Click here to watch

video.

2) An artist conception of the SGR 1806-20 magnetar

including magnetic field lines. After the initial flash, smaller

pulsations in the data suggest hot spots on the rotating magnetar’s

surface. The data also shows no change in the magentar’s rotation

after the initial flash. Click here to watch

video.

3) Radio data shows a very active area around

SGR1806-20. The Very Large Array radio telescope observed ejected

material from this Magnetar as it flew out into interstellar space.

These observations in the radio wavelength start about 7 days after

the flare and continue for 20 days. They show SGR1806-20 dimming in

the radio spectrum. Click here to watch

video.

4) SGR-1806 is an ultra-magnetic neutron star,

called a magnetar, located about 50,000 light years away from Earth in

the constellation Sagittarius. Click here to watch

video.

5) Swift is a first-of-its-kind multi-wavelength

observatory dedicated to the study of gamma ray burst (GRB) science.

Its three instruments will work together to observe GRBs and

afterglows in the gamma ray, X-ray, ultraviolet, and optical

wavebands. Swift is designed to solve the 35-year-old mystery of the

origin of gamma-ray bursts. Scientists believe GRB are the birth cries

of black holes. Click here to watch

video.

6) NASA’s Swift satellite was successfully launched

Saturday, November 20, 2004 from the Cape Canaveral Air Force Station,

Fla. Click here to watch

video.

Other

observatories and scientific representatives include:

Additional

information about magentars and soft gamma ray repeaters

can be found at Dr. Robert Duncan’s web site located at the University

of Texas at Austin: http://solomon.as.utexas.edu/~duncan/magnetar.html

Huge explosion traced to

exotic star

by

Jim Giles

News -

Published online: 18 February 2005

from Nature Website

Astronomers

pinpoint source of unprecedented radiation surge.

The

rotating, highly-magnetized neutron star undergoing a ’quake’ at its

surface. Click here to see animation.

A cataclysmic ’starquake’ is

thought to have caused a flare of radiation that ripped past the Earth

on 27 December, battering instruments on satellites and lighting up our

atmosphere.

Scientists say this is the biggest blast of

gamma and X-rays they have ever observed in our corner of

the Universe. They believe the flare came from a bizarre object just 20

kilometers wide on the other side of the Galaxy.

"This is a

once-in-a-lifetime event," says Rob Fender of Southampton

University, UK, one of the researchers studying data on the flare.

"The object released more energy in a tenth of a second than the Sun

emits in 100,000 years."

Data from

satellites and ground-based telescopes have pinpointed the origin of the

burst as SGR 1806-20, a ’magnetar’ around 50,000 light-years away in the

constellation of Sagittarius. Magnetars are extremely dense,

small stars with magnetic fields at least a thousand trillion times

stronger than the Earth’s. They are a type of neutron star, the compact

remnant of a collapsed sun.

Huge explosion traced to exotic

star

Astronomically speaking, this was in our

backyard.

Bryan Gaensler

Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics

from Nature Website

The flare may

have been caused by a quake on the surface of SGR 1806-20, suggest

researchers. The quake would have disturbed the star’s magnetic field,

creating an explosion that was the brightest ever detected beyond our

Solar System.

It is

possible that similar flares have been misinterpreted in the past.

Analogous gamma ray bursts have been detected, but they were assumed to

come from very distant objects beyond our galaxy.

A

satellite launched last November is ideally positioned to resolve the

issue. NASA’s Swift Gamma Ray Burst Mission is designed to locate and

measure bursts. "Answers to these questions could come any day now that

Swift is in orbit," says Neil Gehrels of NASA’s Goddard Space

Flight Center in Maryland.

Safe

distance

Fortunately for life on Earth, the nearest known

magnetar is about 13,000 light years away - too far for any

future burst to damage the planet. The radiation burst from a closer

explosion could, for example, wipe out the ozone layer.

"Astronomically speaking, this was in our backyard," says Bryan

Gaensler of the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics in

Cambridge, Massachusetts, and an author of a paper about the burst

that has been accepted for publication in Nature. "If it were in our

living room, we’d be in big trouble."

Blast Affected Earth

From Halfway Across The Milky Way

Cambridge MA (SPX) Feb 21, 2005

from SpaceDaily Website

Forget

"Independence Day" or "War of the Worlds." A monstrous cosmic explosion

last December showed that the earth is in more danger from real-life

space threats than from hypothetical alien invasions.

The

gamma-ray flare, which briefly outshone the full moon, occurred within

the Milky Way galaxy. Even at a distance of 50,000 light-years, the

flare disrupted the earth’s ionosphere.

If such a

blast happened within 10 light-years of the earth, it would destroy the

much of the ozone layer, causing extinctions due to increased

radiation.

"Astronomically speaking, this explosion happened in our

backyard. If it were in our living room, we’d be in big trouble!"

Said

Bryan Gaensler (Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics),

lead author on a paper describing radio observations of the

event.

Gaensler headed one of two teams reporting on this

eruption at a special press event today at NASA headquarters. A

multitude of papers are planned for publication.

The giant

flare detected on December 27, 2004, came from an isolated,

exotic neutron star within the Milky Way. The flare was more

powerful than any blast previously seen in our galaxy.

"This might

be a once-in-a-lifetime event for astronomers, as well as for a

neutron star," said David Palmer of Los Alamos National

Laboratory, lead author on a paper describing space-based observations

of the burst.

"We

know of only two other giant flares in the past 35 years, and this

December event was one hundred times more

powerful."

NASA’s newly

launched Swift satellite and the NSF-funded Very Large Array (VLA) were

two of many observatories that observed the event, arising from neutron

star SGR 1806-20, about 50,000 light years from Earth in the

constellation Sagittarius.

Neutron stars form from collapsed stars. They are

dense, fast-spinning, highly magnetic, and only about 15 miles in

diameter. SGR 1806-20 is a unique neutron star called a magnetar,

with an ultra-strong magnetic field capable of stripping information

from a credit card at a distance halfway to the Moon.

Only about 10

magnetars are known among the many neutrons stars in the Milky

Way.

"Fortunately, there are no magnetars anywhere near the earth.

An explosion like this within a few trillion miles could really ruin

our day," said graduate student Yosi Gelfand (CfA), a co-author

on one of the papers.

The

magnetar’s powerful magnetic field generated the gamma-ray flare in a

violent process known as magnetic reconnection, which releases huge

amounts of energy. The same process on a much smaller scale creates

solar flares.

"This

eruption was a super-super-super solar flare in terms of energy

released," said Gaensler.

Using the

VLA and three other radio telescopes, Gaensler and his

team detected material ejected by the blast at a velocity three-tenths

the speed of light. The extreme speed, combined with the close-up view,

yielded changes in a matter of days.

Spotting

such a nearby gamma-ray flare offered scientists an incredible

advantage, allowing them to study it in more detail than ever before.

"We can see

the structure of the flare’s aftermath, and we can watch it change

from day to day. That combination is completely unprecedented," said

Gaensler.

Headquartered

in Cambridge, Mass., the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics

(CfA) is a joint collaboration between the Smithsonian Astrophysical

Observatory and the Harvard College Observatory. CfA scientists,

organized into six research divisions, study the origin, evolution and

ultimate fate of the universe.

Distant explosion breaks

brightness records

by Maggie

McKee

19:00 18 February 2005

from NewScientist

Website

Several dozen

satellites around Earth, and one orbiting Mars, detected a flash

of high-energy photons - known as gamma rays - on 27 December

2004. The 0.25-second flash was so bright it overwhelmed the

detectors on many satellites - making an energy measurement impossible -

and disrupted some radio communication on Earth.

"It was so

bright, it came right through the body of the Swift satellite, even

though Swift wasn’t pointed at the object," says John Nousek,

mission director for NASA’s Swift spacecraft - launched

especially to detect gamma-ray bursts (GRBs) - at Pennsylvania

State University, US.

The brief

flash was followed by a fainter afterglow of gamma rays lasting for

about 500 seconds, which showed a recurring signal every 7.5 seconds.

That signal led scientists using Europe’s INTEGRAL spacecraft to trace

the source of the "superflare" to a dead star - called a neutron

star - known to spin at that rate. Measurements of the distance to

the star - called SGR 1806-20, range from 30,000 to 50,000 light years

from Earth.

That

relatively small distance, coupled with an accurate energy measurement

by NASA’s RHESSI satellite, means the explosion was not as

powerful - at source - as more distant bursts linked with black holes.

Nevertheless, it "may have sterilized any planets within a few light

years of it", says Rob Fender, an astronomer at Southampton

University, UK, who is studying the lingering radio emission from the

flare. "This may be a once-in-a-lifetime event both for astronomers and

for the neutron star itself."

Clean credit card

But Christopher Thompson, an

astrophysicist at the Canadian Institute for Theoretical Physics, says

that may not be so. The neutron star in question is rare

magnetar, with a magnetic field so strong it could wipe a credit

card clean from a distance of 160,000 kilometers. And this

magnetar is even rarer yet, one of three "soft gamma repeaters"

(SGRs) in the Milky Way.

SGRs tend to release low-energy flares of gamma rays

sporadically, but more energetic bursts have been observed twice before

- in 1998 and 1979. But the energy in the initial 0.25-second burst from

the most recent flare was 100 times that of the two previous

superflares.

But

Thompson, who worked on the most accepted magnetar model, says:

"I wasn’t

shocked at the energy it was putting out. The total energy implied by

the models is enough to power a dozen or more of these events in the

life of one magnetar."

Superflares

may occur when tightly wrapped magnetic fields inside the magnetar start

to "untwist". This briefly rips loose some magnetic fields outside the

star, releasing a "fireball" of particles, and light that astronomers

see as a bright flash of gamma rays.

Extreme distances

If this flare had been even farther away -

up to 100 million light years or so - it would have looked

"indistinguishable" from a short GRB - a cosmic phenomenon that

has baffled astronomers for years.

Short GRBs

are blasts of high-energy gamma rays that last less than two seconds.

Astronomers are unsure of their cause but think they have a different

origin than "long" GRBs - lasting for several seconds or minutes - which

are thought to be created during the birth of black holes.

This

latest observation leads David Palmer, a Swift team member at Los

Alamos National Laboratory in New Mexico, US, to say:

"I’m fairly

confident that soft gamma repeaters account for at least some short

gamma-ray bursts."

Neil

Gehrels, principal investigator for Swift at NASA, says Swift should

be able to help settle the debate about short GRBs. Swift will study

both SGRs and short GRBs, having the capability to quickly respond to

short GRBs in order to locate them in space.

But he

laments: "It’s very unlikely we’re going to see another one of these

supergiant flares."

Related Articles

• Massive exploding stars create rare

magnetars 05 February 2005

• Swift mission sees its first gamma ray

bursts 07 January 2005

• Superbright gamma ray burst may be

closest ever 04 April

2003

Weblinks

• Swift, NASA

• INTEGRAL, ESA

• RHESSI, NASA

Monster star burst was

brighter than full Moon: astronomers

AFP

Fri

Feb 18, 2005 2:40 pm

from Able2Know Website

PARIS (AFP) -

Stunned astronomers described the greatest cosmic explosion ever

monitored -- a star burst from the other side of the galaxy that was

briefly brighter than the full Moon and swamped satellites and

telescopes.

The high-radiation flash, detected last December 27,

caused no harm to Earth but would have literally fried the planet had it

occurred within a few light years of home.

Normally reserved

skywatchers struggled for superlatives.

"This is a

once-in-a-lifetime event," said Rob Fender of Britain’s

Southampton University.

"We have observed an object only 20

kilometers (12 miles) across, on the other side of our galaxy,

releasing more energy in a 10th of a second than the Sun

emits in 100,000 years."

"It was the mother of all magnetic

flares -- a true monster," said Kevin Hurley, a research physicist at

the University of California at Berkeley.

Bryan

Gaensler of the United States’ Harvard-Smithsonian Center for

Astrophysics, described the burst as,

"maybe a

once per century or once per millennium event in our

galaxy.

"Astronomically speaking, this explosion happened in

our backyard. If it were in our living room, we’d be in big

trouble."

The blast was

caused by an eruption on the surface of a known, exotic kind of

neutron star called SGR 1806-20, located about 50,000 light

years from Earth in the constellation of Sagittarius and about three

billion times farther from us than the Sun.

A neutron star is the

remnant of a very large star near the end of its life -- a tiny,

extraordinarily dense core with a powerful magnetic field, spinning

swiftly on its axis.

When these ancient star cores finally run

out of fuel, they collapse in on themselves and explode as a

supernova.

There are millions of neutron stars in the Milky Way

but, so far, only a dozen have been found to be "magnetars":

neutron stars with an ultra-powerful magnetic

field.

Magnetars have have a magnetic field measuring

about 1,000 trillion gauss, hundreds of times more powerful than that of

any other object in the Universe.

To give an idea of this in

earthly terms, the field is so powerful that it could strip the data off

a credit card at a distance of 200,000 kilometers (120,000

miles).

SGR 1806-20 is an even rarer bird. It is one of only four

known "soft gamma repeater" (SGR) magnetars, so

called because they flare up randomly and release gamma rays in a

mammoth burst.

Why this happens is unknown. One theory is that

the energy release comes from magnetic fields which wrestle and overlap

because of the star’s spin and then snap back and reconnect, creating a

"starquake" rather like the competing faults that cause an

earthquake.

What is sure, though, is that the outpouring of

energy is massive.

The SGR 1806-20 spewed out about

10,000 trillion trillion watts, or about 100 times brighter than any

of the several "giant flares" that have been previously

recorded.

Despite this energy loss, the strange star did not even

pause, Britain’s Royal Astronomical Society (RAS)

said.

"SGR

1806-20 spins once in only 7.5 seconds. Amazingly, the December 27

event did not cause any slowing of its spin rate, as would be

expected," the RAS said.

The flare,

detected by satellites and telescopes operated by NASA (news -

web sites) and Europe, was so powerful that it bounced off the Moon and

lit up the Earth’s upper atmosphere. For over a tenth of the second, it

was actually brighter than a full Moon, and briefly overwhelmed delicate

sensors, RAS said.

Two science teams, formed by observations

provided by 20 institutes around the world, will report on the blast in

a forthcoming issue of the British weekly journal Nature.

Many

questions will be thrown up by the event, including the intriguing

speculation that the dinosaurs may have been wiped out by a similar,

closer gamma-ray explosion 65 million years ago, and not by climate

change inflicted by an asteroid impact.

"Had this

happened within 10 light years of us, it would have severely damaged

our atmosphere and possibly have triggered a mass extinction," said

lead-author Gaensler.

The good

news, he noted, is that the nearest known magnetar to Earth,

1E 2259+586, is about 13,000 light years

away.

Magnetar flare blitzed

Earth Dec. 27, could solve cosmic

mysteries

Co-authors

with Hurley, Boggs, Duncan and Thompson were

D. M. Smith of the UC Santa Cruz physics department, RHESSI and

Wind principal investigator and Space Sciences Laboratory Director

Robert Lin, and teams of U.S., Swiss, Russian, and German

scientists

This information is

co-released with The University of California, Berkeley, and co-insides

with a NASA Space Science Update

18 February

2005

from McDonaldObservatory Website

Austin, Texas

— Astronomers

around the world recorded late last year a powerful explosion of

high-energy X-rays and gamma rays — a split-second flash from the other

side of our galaxy that was strong enough to affect the Earth’s

atmosphere. The flash, called a soft gamma repeater flare, reached Earth

on Dec. 27 and was detected by at least 15 satellites and spacecraft

between Earth and Saturn, swamping most of their detectors.

Thought

to be a mighty cataclysm in a super-dense, highly magnetized star called

a magnetar, it emitted as much energy in two-tenths of a second

as the sun gives off in 250,000 years. Robert C. Duncan of the

University of Texas at Austin originally proposed and developed the

magnetar theory, along with Christopher Thompson of the

Canadian Institute of Theoretical Astrophysics.

"This is

a key event for understanding magnetars," Duncan said. Its

intrinsic power was a thousand times greater than the power of all other

stars in the galaxy put together, and at least 100 times the power of

any previous magnetar outburst in our galaxy. It was ten thousand

times brighter than the brightest supernova.

Duncan and Thompson worked with Kevin

Hurley, a research physicist at UC Berkeley who leads a major

international team studying the event, to understand the immense power

of the Dec. 27 flare. "It was the mother of all magnetic flares - a true

monster," Hurley said.

The

team’s observations and analysis are summarized in a paper that has been

submitted for publication in the journal Nature.

"Soft

gamma repeater" bursts — pinpoint flashes of highly energetic X-rays and

low-energy (soft) gamma rays coming repeatedly from one place in the sky

— were first noticed in 1979 and remained a mystery until Duncan and

Thompson proposed in 1992 that they originate from magnetically powered

neutron stars, or magnetars. Formed by the collapsing core of a

star throwing off its outer layers in a supernova explosion, neutron

stars are extremely dense, with more mass than in the Sun packed into a

ball about 10 miles across. Many neutron stars spin rapidly. These

spinning neutron stars, some rotating a thousand times a second, signal

their presence by the emission of pulsed radio waves, and are called

pulsars.

According

to Duncan, magnetars are a special kind of neutron

star. They are born rotating very quickly, which causes their

magnetic fields to get amplified. But after a few thousand years, their

intense magnetic field slows their spin to a more moderate period of one

rotation every few seconds. The magnetic fields both inside and outside

the star twist, however, and according to the theory these intense

fields can stress and move the crust much like shearing along the San

Andreas Fault. These magnetic fields are a quadrillion — a million

billion — times stronger than the field that deflects compass needles at

the Earth’s surface.

The shear

moves the crust around and the magnetic fields are tied to the crust,

generating twists in the magnetic field that can sometimes break and

reconnect in a process that sends trapped positrons and electrons flying

out from the star, annihilating each other in a gigantic explosion of

hard gamma rays.

The flare

observed Dec. 27 originated about 50,000 light years away in the

constellation Sagittarius, which means that the magnetar sits

directly opposite the center of our galaxy from the Earth in the disk of

the Milky Way Galaxy.

As the

radiation stormed through our solar system, it blitzed at least 15

spacecraft, knocking their instruments off-scale whether or not they

were pointing in the magnetar’s direction. One Russian satellite,

Coronas-F, detected gamma rays that had bounced off the Moon.

The flare

also ripped atoms apart, ionizing them, in much of the Earth’s

ionosphere for five minutes, to a deeper level than even the biggest

solar flares do, an effect noticed via its effect on long-wavelength

radio communications. Such events are unlikely to pose a danger to the

Earth because the chances that one would be close enough to the Earth to

cause serious disruption are exceedingly small.

Hurley and his team combined information from many

spacecraft, including neutron and gamma-ray detectors aboard Mars

Odyssey and many near-Earth satellites, in order to localize it to a

spot well-known to astronomers: a magnetar known as SGR

1806-20. This position was accurately confirmed by radio astronomers

at the Very Large Array in Socorro, N.M., who studied the fading radio

afterglow of the event and obtained important information about the

explosion.

The

tremendous power of the event has suggested a novel solution to a

long-standing mystery — the origins of a strange phenomenon known as

"Short-Duration Gamma Ray Bursts." Hundreds of brief, mysterious

flashes of high-energy radiation from deepest space, lasting less than

two seconds, have been measured and recorded over decades, but nobody

knew what they were.

The

similarity between the Dec. 27 burst and these short-duration bursts

lies in the brief spike of hard gamma rays that arrives first and

carries almost all the energy. In the recent burst, for example, the

hard spike lasted only two-tenths of a second. This was followed by a

"tail" of X-rays that lasted over six minutes. As the tail faded, its

brightness oscillated on a 7.56 second cycle, the known rotation period

of the magnetar.

According

to Duncan and Thompson’s theory, the oscillating X-ray

tail that followed was due to a residue of electrons, positrons and

gamma-rays trapped in the magnetar’s magnetic field. Such a hot "trapped

fireball" shrinks and evaporates over minutes, as electrons and

positrons annihilate. The measurements of Hurley’s team corroborate this

picture. The tail’s brightness appears to oscillate because the fireball

is stuck to the surface of the rotating star by the magnetic field, so

it rotates with the star like a lighthouse beacon.

Duncan and his team argue that the hard initial spike

of these giant flares is so bright that it can be detected from very far

away, meaning that some of the short flares we see are from other

galaxies, though the soft X-ray tails are too faint to be

seen.

Duncan

and his collaborators predict that if a magnetar flares as

brightly as the December 27 event within 100 million light-years

of Earth, astronomers should be able to detect it. Texas astronomers

John Scalo and Sheila Kannappan helped Duncan

estimate the rate at which such distant flares might be seen. They

estimated that of order 40% of the short bursts previously observed

could have been such magnetar bursts. There is a good probability that

the newly-launched Swift satellite will see a magnetar burst

once a month.

Launched

in November 2004 and gathering data only since January, Swift is

designed to automatically turn its X-ray telescope toward a burst in

order to accurately pin down its position.

Duncan’s

team estimates that Swift will spot an abundance of magnetars lurking in

other galaxies. In some cases, Swift’s X-ray telescope may even catch

the oscillating tail and measure the rotation period of the faraway

star.

"Swift

will open up a new field of astronomy: the study of extragalactic

magnetars," Duncan said.

Huge ’star-quake’ rocks

Milky Way

from 12thArmonic Website

It turns out that the 26th and

27th of December were not only turbulent for our planet, but

turbulent for our galaxy too. The explosion took place in the

constellation of Sagittarius. I’m very grateful to fixed star expert

Diana K Rosenberg for calculating the position and time of the

explosion, which in astrological tropical zodiac terms occurred at

01CAP28; LAT 3N 25 53; DECL 19S20; RA 18 06 18. It occurred Dec 27,

2004, at 21:30:26 UT.

BBC

- Astronomers

say they have been stunned by the amount of energy released in a star

explosion on the far side of our galaxy, 50,000 light-years away. The

flash of radiation on 27 December was so powerful that it bounced off

the Moon and lit up the Earth’s atmosphere. The blast occurred on the

surface of an exotic kind of star - a super-magnetic neutron star called

SGR 1806-20.

If the

explosion had been within just 10 light-years, Earth could have suffered

a mass extinction, it is said.

"We figure

that it’s probably the biggest explosion observed by humans within our

galaxy since Johannes Kepler saw his supernova in 1604," Dr

Rob Fender, of Southampton University, UK, told the BBC News

website.

One

calculation has the giant flare on SGR 1806-20 unleashing about

10,000 trillion trillion trillion watts.

"This is a

once-in-a-lifetime event. We have observed an object only 20km across,

on the other side of our galaxy, releasing more energy in a 10th of a

second than the Sun emits in 100,000 years," said Dr

Fender.

VLA Probes Secrets of Mysterious

Magnetar

February 18,

2005

from NationalScienceFoundation

Website

|

This graphic illustrates the VLA measurements

of the exanding fireball from the Dec. 27, 2004, outburst of the

magnetar SGR 1806-20. Each color indicates the observed size of

the fireball at a different time. The sequence covers roughly

three weeks of VLA observing. The outline of the fireball in each

case is not an actual image, but rather a "best-fit" model of the

shape that best matches the data from the VLA.

Credit: G.B.

Taylor, NRAO/AUI/NSF |

A giant flash

of energy from a supermagnetic neutron star thousands of light-years

from Earth may shed a whole new light on scientists’ understanding of

such mysterious "magnetars" and of gamma-ray bursts. In the

nearly two months since the blast, the National Science Foundation’s

Very Large Array (VLA) telescope has produced a wealth of

surprising information about the event, and "the show goes on," with

continuing observations.

The blast

from an object named SGR 1806-20 came on Dec. 27, 2004, and was

first detected by orbiting gamma-ray and X-ray telescopes. It was the

brightest outburst ever seen coming from an object beyond our own solar

system, and its energy overpowered most orbiting telescopes.

The burst of

gamma rays and X-rays even disturbed the Earth’s ionosphere, causing a

sudden disruption in some radio communications.

While the intensely

bright gamma ray burst faded in a matter of minutes, the VLA and other

radio telescopes have been tracking the explosion’s "afterglow" for

weeks, providing most of the data astronomers need to figure out the

physics of the blast.

A

magnetar is a superdense neutron star with a magnetic

field thousands of trillions of times more intense than that of the

Earth. Scientists believe that SGR 1806-20’s giant burst of energy was

somehow triggered by a "starquake" in the neutron star’s crust

that caused a catastrophic disruption in the magnetar’s magnetic field.

The magnetic disruption generated the huge burst of gamma rays and

"boiled off" particles from the star’s surface into a rapidly expanding

fireball that continues to emit radio waves for weeks or

months.

The

VLA first observed SGR 1806-20 on Jan. 3, and has been

joined by other radio telescopes in Australia, the Netherlands, and

India. Scientific papers prepared for publication based on the first

month’s radio observations report a number of key discoveries about the

object.

Scientists

using the VLA have found:

• The

fireball of radio-emitting material is expanding at roughly one-third

the speed of light.

• The expanding fireball is elongated, and may

change its shape quickly.

• Alignment of the radio waves

(polarization) confirms that the fireball is not spherical.

• The

flare emitted an amount of energy that represents a significant

fraction of the total energy stored in the magnetar’s magnetic

field.

Of the dozen

or so magnetars known to astronomers, only one other has been seen to

experience a giant outburst. In 1998, SGR 1900+14 put out a blast

similar in many respects to SGR 1806-20’s, but much weaker.

National

Radio Astronomy Observatory (NRAO) astronomer Dale Frail

observed the 1998 outburst and has been watching SGR 1806-20 for a

decade. Both magnetars are part of the small group of objects

called soft gamma-ray repeaters, because they repeatedly

experience much weaker outbursts of gamma rays.

In early

January, he was hosting a visiting college student while processing the

first VLA data from SGR 1806-20’s giant outburst.

"I

literally could not believe what I was looking at," Frail said.

"Immediately I could see that this flare was 100 times stronger than

the 1998 flare, and 10,000 times brighter than anything this object

had done before."

"I

couldn’t stay in my chair, and this student got to see a real, live

astronomer acting like an excited little kid," Frail

said.

The

excitement isn’t over, either. "The show goes on and we continue to

observe this thing and continue to get surprises," said Greg

Taylor, an astronomer for NRAO and the Kavli Institute of

Particle Astrophysics and Cosmology in Stanford, Calif..

One

VLA measurement may cause difficulties for scientists trying to

fit SGR 1806-20 into a larger picture of gamma ray bursts (GRBs).

GRBs, seen regularly from throughout the universe, come in two main

types--very short bursts and longer ones. The longer ones are generally

believed to result when a massive star collapses into a black hole,

rather than into a neutron star as in a supernova explosion.

The strength

and short duration of SGR 1806-20’s December outburst has led some

astronomers to speculate that a similar event could be seen out to a

considerable distance from Earth. That means, they say, that

magnetars may be the source of the short-period

GRBs.

That

interpretation is based to some extent on a previous measurement that

indicates SGR 1806-20 is nearly 50,000 light-years from Earth. One team

of observers, however, analyzed the radio emission from SGR 1806-20 and

found evidence that the magnetar is only about 30,000 light-years

distant. The difference, they say, reduces the likelihood that SGR

1806-20 could be a parallel for short-period GRBs.

In any case,

the wealth of information astronomers have gathered about the tremendous

December blast makes it an extremely important event for understanding

magnetars and GRBs.

Continuing Earth Changes

Cripple American Submarine and Pose New Dangers for the American

Continents

by

Sorcha Faal, and as reported to her Russian

Subscribers

January

10, 2005

from WhatDoesItMean Website

Continued energy surges, and as yet still

unexplained by Western scientists, continue to bombard the earth’s

Southern Hemispheric Regions this morning causing many widespread

and anomalous events throughout the world and affecting all of its

peoples.

Western media sources are presently reporting the dire

circumstances surrounding the United States Los Angeles Class Nuclear

Submarine San Francisco and the latest reports are saying that one

crewman has died and ‘23 other crew members are being treated aboard for

injuries including broken bones, bruises and lacerations’.

The

BBC also reports in this article that,

“The US

Navy said it did not know what the vessel had struck and was

investigating severe damage to the outside of the

submarine.”

Not being

reported by the Western media though is that the USS San

Francisco (SSN 711) is part of the United States Navy’s Pacific

Fleet, and a part of what is known as Submarine Squadron Fifteen based

out of the US Territory of Guam, located in the Mariana Islands Region

of the Pacific Ocean.

The significance of this lies in the

eruption on Anatahan Island, a part of the Mariana Islands and in

the ‘patrol zone’ of the USS San Francisco.

As related to us by

one Russian Naval Official,

“Imagine

you walking around your house at night with the lights off and someone

had re-arranged the furniture, make no mistake about it, the American

submariners ‘know’ their courses too well and are too highly trained

for this to happen suddenly. Some extreme geologic ‘change’ had

to have happened for this accident to occur.”

Could this

‘extreme geologic change’ have been this eruption?

As reported

in the Western media regarding this event we hear,

“The

volcano’s activity intensified beginning Tuesday and Wednesday last

week after months of extremely low seismic activities, which followed

the second batch of eruptions from April to June last year. The

volcano on Anatahan first erupted after centuries of dormancy

on May 10, 2003, with ash plume rising to more than 30,000

feet.”

We are also

continuing to receive reports of meteor fireballs entering the

earth’s atmosphere. Yesterday another such sighting was reported as

occurring in the United States region of Alaska, and where it is said,

“It

streaked quickly from the west to the east in a steep downward arc,

and soon wasn’t visible behind the mountains.”

More

information also continues to be received by us also relating to my

December 28, 2004 report, Evidence for Sumatra 9.0 Quake Leans towards

Meteorite Strike.

In one research report by the United States

National Geophysical Data Center (NGDC) it clearly states, and in

apparent contradiction to the known facts about The Great Tsunami of

2004, that,

“In the

Indian Ocean, however, the Indo-Australian plate is being subducted

beneath the Eurasian plate at its east margin. Therefore, most

tsunamis generated in this area are propagated toward the

southwest shores of Java and Sumatra, rather than into the Indian

Ocean.”

As recent

events have occurred however we know this not to be the case due to the

fact that the waves propagated out from a ‘center’ to all areas of the

Indian Ocean, to even the African Coast and beyond.

Numerous, yet

conflicting, Western media reports also continue to be generated about

this cataclysmic event with no regard to science fact but rather relying

on speculation alone.

Reports are varying to many extremes of sea

floor horizontal and/or vertical movement, such as one report that

states, “slippage occurred along about 1,200 km of the interface between

the tectonic plates”, and another that states that it was, “…a

600-mile-long (965km) rupture that generated a 35ft vertical

displacement in the sea floor.”

But the differences in how many

kilometers of vertical displacement did or did not occur, or how high or

low various parts of the sea floor rose or fell are not as important as

to how fast these assertions of fact were being spread by the Western

media sources.

They in fact began within hours of the cataclysm

occurring, with no scientific research being conducted and in

contradiction to what the United States National Geophysical Data Center

had reported and Prof Ravinder Kumar of the Centre of Advance

Studies in Geology, Punjab University who has said, “There is no

historic record of a tsunami in the Indian Ocean.”

This

information alone does not constitute proof of a meteorite strike

being the cause of this cataclysmic, but neither do the pronouncements

by the Western media stating the cause as being an earthquake

event. The behavior of the waves in the Indian Ocean though do

suggest a meteorite due to their concentric nature of flowing throughout

the oceans basin, where if these were caused by an earthquake would have

been omni or bi directed only as scientists have previously predicted,

and particularly in a region where no historical reports of a tsunami

had ever been recorded.

Not being connected in the Western Media

about this event either was its precursor which occurred in the

Macquarie Island region of Antarctica and was measured as an 8.2

event on the Richter scale. (An 8.2 Richter event is equal to 3 billion

tons of TNT and the 9.0 event in the Indian Ocean was equal to 32

billion tons.)

But released

almost simultaneously with the Antarctica 8.2 event was a report from

the United States space organization NASA’s Near Earth Object Program in

an ‘Asteroid Alert’ which in part said,

“For

comparison, the Barringer Meteor Crater in northern

Arizona is thought to have been created by an iron meteorite

between 30 and 100 meters in diameter. Its impact would have released

energy equivalent to about 3.5 million tons of

TNT.”

More

interesting in the light of these recent events are that these two

events have more in common than their historically rare power in that

both the Antarctica event and the Indian Ocean event are connected by

their sameness in both geological and magnetic anomalous features, and

as previously mapped by scientists.

One such other area on the

earth is known as the Cayman Trough and is located in the Northwest

Caribbean Sea.

A number of the world’s top scientists in their

fields have reported on this region in a report that in part

says,

“We review

the plate tectonic evolution of the Caribbean area based on a revised

model for the opening of the central North Atlantic and the South

Atlantic, as well based on an updated model of the motion of the

Americas relative to the Atlantic-Indian hotspot reference frame. We

focus on post-83 Ma reconstructions, for which we have combined a set

of new magnetic anomaly data in the central North Atlantic between the

Kane and Atlantis fracture zones with existing magnetic anomaly data

in the central North and South Atlantic oceans and fracture zone

identifications from a dense gravity grid from satellite altimetry to

compute North America-South America plate motions and their

uncertainties.”

As we are all

aware, the largest magnetic anomalous area in the world is located in

Russia and is named the Kursk Satellite Magnetic Anomaly

(KMA), and in the memory of our fallen heroes from the great

Russian Submarine Kursk of the same naming.